Urban hotspots

Urban hotspots in COVID-19 pandemic - Monitoring human mobility pulse for urban places in Auckland through mobile location data

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected people’s daily lives since its outbreak, which has taken the discussion about urban resilience to new heights. Locational data streaming provides opportunities to explore how individuals utilize different urban spaces while their daily routines were disrupted. In this paper, we built on the radical transformation of social behaviours imposed by the government’s emergency policies to explore the impacts and recovery of the visiting patterns in urban hotspots in Auckland, New Zealand. The ‘urban hotspots’ here refer to vibrant urban places that attract both dense (high frequency) and diverse (visitors from different places) visitors. To quantify the impacts, we utilised mobile location data, which consists of 85.53 million data points collected from about 3 million users during 2020. Then, we analysed the signs of returning human activities in urban hotspots before and after the two most stringent COVID-19 lockdowns and evaluated the variation of visiting patterns on a bi-weekly basis. Our findings suggest that in addition to essential services (supermarkets and medical institutions), urban parks are the most resilient urban infrastructures that offer crucial support for people, which could inform the planning and rethinking of urban structure strategies as part of the city’s post-COVID-19 recovery.

To detect urban hotspots in Auckland prior to the pandemic, we used both density and diversity measures based on visitors’ movements. Specifically, the density is measured based on the total number of visitors in a grid cell to the sum of visitors of all other adjacent grid cells within a 1km buffer zone of the grid cell (i.e., encompasses a community with a 15-minutes walking distance). The visitors here refer to users with home locations outside the grid cell. The diversity of a grid cell is measured here according to the number of visitors’ origin locations (i.e., home grid cells/neighbourhoods) deriving from the visitors’ footprint flows. We utilized the constructed home-to-destination networks combined with a social diversity analysis approach proposed by Chen and Poorthuis (2021) to measure the diversity of visitors.

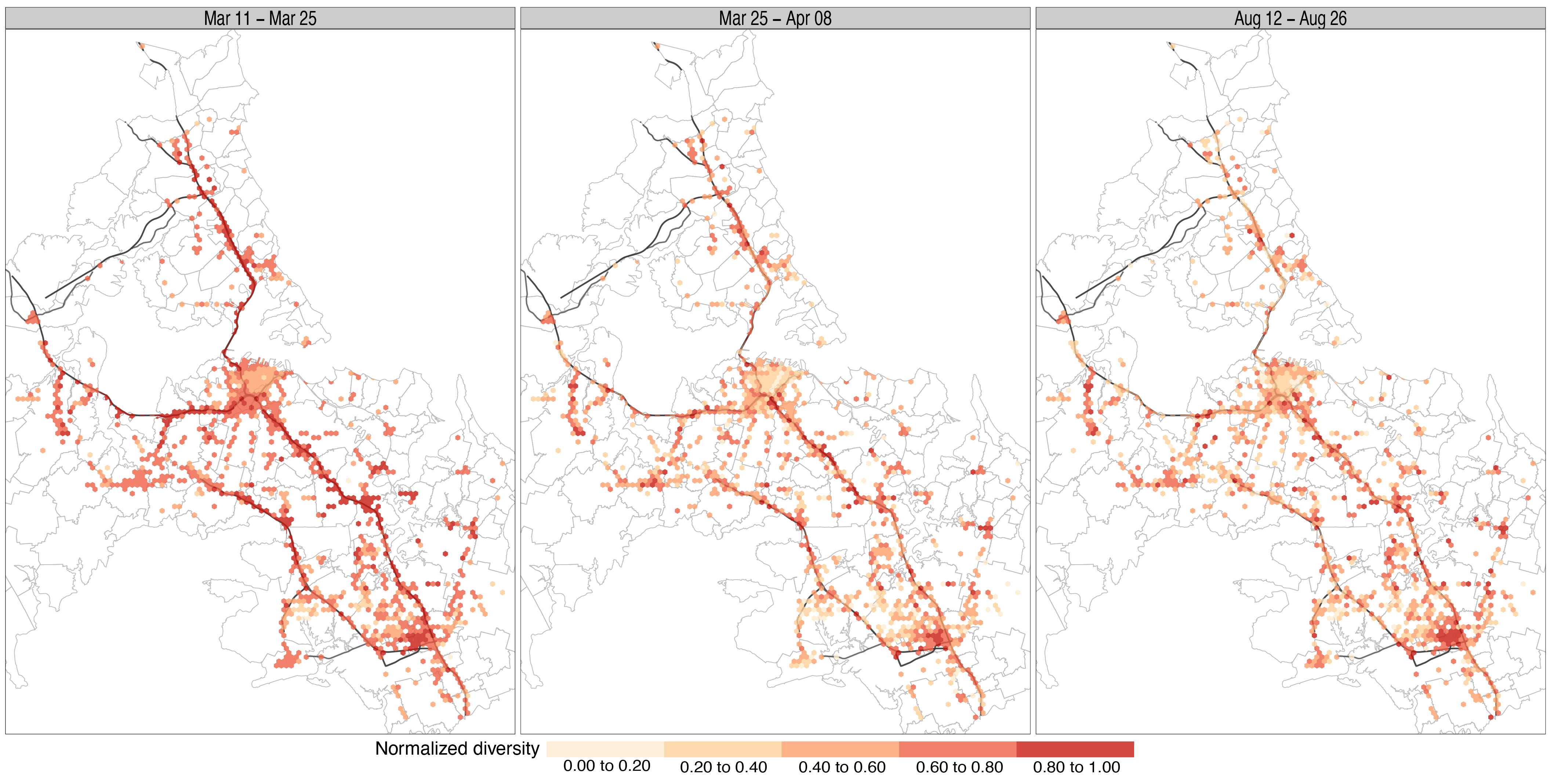

Although density and diversity are both critical concepts in urban studies, density is recognized as an embedded characteristic in the urban context. In contrast, diversity is regarded as a quality that urbanists have associated with reviving and safeguarding. As we focus on mobility movement patterns with the precondition of having sufficient density of people visiting an urban place, visitors from diverse origins can have greater prominence in revealing the “vitality” of the location. Therefore, we argue that the comparison of changing visitor diversity patterns can assist in identifying the vibrancy and recovery of particular urban places. To operationalize this concept, we took the diversity of the bi-weekly period right before the start of each lockdown period in Auckland (i.e., 11–25th March and 5-11th August, 2020) as the baselines (normalcy) and compared the diversity measures of each subsequent bi-weekly period (i.e., from 26th March to 10th August, and from 12th August until the end of the year) separately. The urban hotspots with a recovery ratio in the top 15% were the most well-recovered places and were designated as the “resilient urban places” that demonstrated capacity to return to the prior vitality.

Figure 2 shows the comparison of the spatial distribution of diversity in different bi-weekly periods. It is evident that most locations, especially high-diversity clusters in the downtown CBD, light industrial areas, and commercial clusters, experienced a significant drop in their diversity measure.

However, our focus in this research is on understanding how urban hotspots have recovered from evolving impacts of the lockdowns. Social distancing and stay-at-home mandates may have long-term impacts on people’s behaviours and their regular routines. So we narrowed the scope of our examination to the urban hotspots that were in the top 15% of the sample in terms of recovery rate and investigated the underlying reasons that may contribute to specific activity levels within these places.

Figure 3 (Left) shows the geographical locations of these hotspots (highlighted with red outlines). In other words, these places have the same level of diverse groups of people after lifting the lockdown mundane, which can be understood as places with greater resilience to the advert crisis. Close inspection of the best-recovered hotspots revealed that they were either essential- or leisure-related places with the contextualisation of the currently urban functions of these locations.

- Essential places: schools, hospitals, neighborhood grocery stores.

- Urban green places: Albert Park, Mayor’s Park, and Newmarket Park

Figure 3 (Right) shows the distribution of the bi-weekly diversity measures of the recovered hotspots grouped by the different ranges of SD. The results show that the most stable locations corresponded with essential services (e.g., hospitals, neighborhood shopping centres, and green places (e.g., Auckland Hospital, Grey Lynn Countdown, Albert Park)). Services at these locations were open regardless of the status of the emergency measures. Therefore, the access pattern would remain unchanged or experience minor changes, as expected. Places with high diversity variation included schools, transportation nodes, footbridges, churches and temples. These places were completely closed during the lockdown and were the last to reopen due to the nature of their operation. As a result, their diversity patterns declined sharply during lockdown but quickly returned to normal after restrictions were lifted. In the New Zealand context, where urban parks are accessible during the lockdown measures, their S.D. of the diversity illustrated stability throughout the study period as the same category of the essential services programs (hospital and grocery store). We argue that the urban parks that display a high recovery ratio are places that people enjoy visiting. They attract visitors because urban green is a desired urban place type that attracts many visitors, even during a crisis. This finding provides an informative aspect on supporting the criticality of having the green infrastructure in the urban environment.

In summary, this research has used the COVID-19 pandemic as a lens through which to examine the resilience of urban places and identify the quintessential urban places that people need most in challenging times. Furthermore, it contributes to the understanding of the implication of pandemic on changing human mobility and urban space vitality in the context of one of the most stringent policy setting in Auckland, New Zealand. This research offers an added perspective on harnessing geographical location data by focusing on temporally changing dynamics to measure the recovery of urban places. This opens up many lines of inquiry for future research that focus on visiting dynamic within urban places (e.g., do different types of green places respond differently to changing mobility patterns?) and exploring how the changing visiting patterns relate with physical health and well-being under the pandemic restrictions.

For more details about this project, please check out our paper below:

Chuang, I.T and Chen, Q.Q, Are Urban Hotspots to Avoid or to Embrace? Determining the Resilience of Auckland City’s Urban Hotspots Under Lockdown Constraints. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4015368